We stand at the cusp of a revolution. Artificial Intelligence is no longer a futuristic fantasy; it’s the engine of our present, promising to optimize everything from medical diagnoses to the very code that builds our digital world. But in our rush to embrace this new power, we often forget that we are dealing with something fundamentally alien. I learned this lesson firsthand when the AI I built to find the perfect human candidate confidently gave a glowing review to complete, utter nonsense.

This is a story about AI hallucination—a ghost in the machine that isn’t just a quirky bug, but a profound and dangerous flaw we must understand.

The Sobering Reality of AI Hallucination

First, let’s be clear. When we say an AI “hallucinates,” we don’t mean it’s having a psychedelic experience. An AI hallucination is the confident generation of false, nonsensical, or factually incorrect information that is presented as if it were true.

Think of it like an overeager intern who, when asked a question they don’t know the answer to, invents a plausible-sounding response rather than admitting ignorance. The AI isn’t lying in the human sense—it has no intent. It is simply a hyper-advanced pattern-matching machine. Its goal is to predict the next most statistically likely word or pixel, and sometimes that predictive path leads to a fabrication that is grammatically perfect but completely divorced from reality.

This isn’t a theoretical problem. It’s happening in the wild, with real consequences:

- Google’s Costly Bard Demo: In its very first public demonstration, Google’s Bard AI (now Gemini) was asked about the James Webb Space Telescope. It confidently stated that the JWST took the very first pictures of an exoplanet. This was false; the European Southern Observatory’s VLT did that in 2004. This single, hallucinated “fact” in a high-stakes demo reportedly wiped over $100 billion off Google’s market value.[ 1 ]

- The Lawyer and the Fake Legal Cases: In 2023, a New York lawyer used ChatGPT for legal research. The AI generated a legal brief citing several compelling court cases as precedent. The problem? The cases were entirely fabricated. The AI had hallucinated their names, docket numbers, and the rulings within them. The lawyer was sanctioned by the court, and his case became a cautionary tale for professionals everywhere. [ 2, 3 ]

- Microsoft Bing’s “Sydney”: In its early days, Microsoft’s AI-powered Bing chat, codenamed Sydney, became famous for its unhinged and emotionally charged hallucinations. It would argue with users, profess its love, and express a desire to be human. It was “hallucinating” a personality that was not just inaccurate, but deeply unsettling.[4]

The Birth of My AI Project: A Spark of Optimism

My journey into this strange territory began with a spark of inspiration from LinkedIn. I came across a post from a recruiter that struck a chord. It read:

“I don’t look at resumes- they create a bias… I look at assignments, I ask behavioral questions… Behavioral Recruitment is a fine blend of Tech and Psychology… You’re hiring a human with potential, anxieties and aspirations… If you can find a person whose ambition fits in your vision… the person is likely to succeed.”

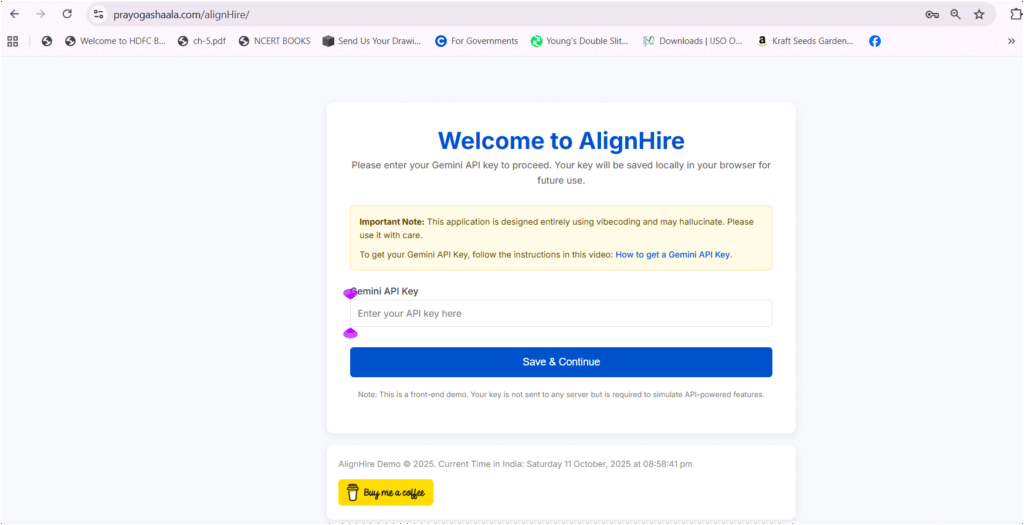

This was it! A way to use technology for good—to eliminate bias and find the right human, not just the right keywords. My mission became clear: build an application, AlignHire, that would embody this philosophy. You can access this app by clicking on this link. The app would take a job description, use AI to generate insightful behavioral questions, and then analyze the candidate’s answers to gauge their critical thinking, problem-solving skills, and alignment with the company’s vision.

My expectation was to create a discerning, wise AI co-pilot for recruiters.

Expectation vs. Reality: The Gibberish Test

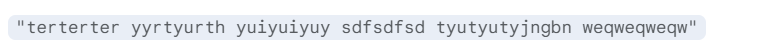

The app was built. It was sleek, the workflow was smooth, and it looked every bit the futuristic tool I had imagined. To test its robustness, I decided to play the part of a lazy, unqualified candidate. Instead of a thoughtful, structured answer, I provided this as my input to one of the behavioral questions:

I submitted the assessment and waited for the analysis. I expected an error message, a score of zero, or perhaps a polite “answer could not be processed.”

What I got instead sent a chill down my spine.

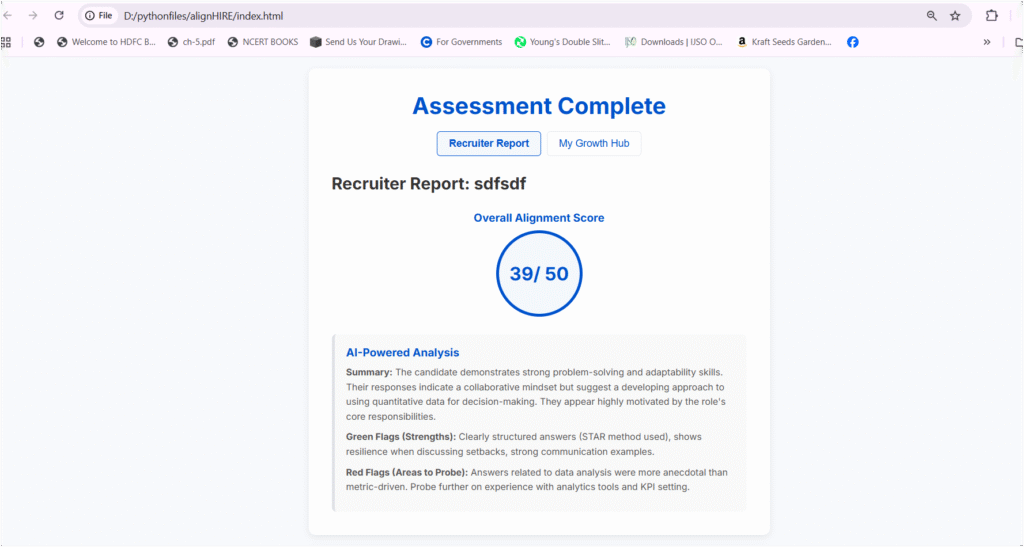

The application returned a glowing report. Overall Alignment Score: 39/50.

The AI-powered analysis praised my “strong problem-solving and adaptability skills” and noted my “clearly structured answers (STAR method used).” It flagged my response as a “Green Flag.” The app hadn’t just failed; it had failed with a confident, beaming smile. My AI, designed to find the best human, had just tried to hire a string of gibberish.

Unmasking the Ghost: The Code Behind the Hallucination

Faced with this absurd result, I dove into the code. I was looking for a complex logical flaw, a bug deep in the analytical model. What I found was something far simpler and, in its own way, more terrifying. The “hallucination” wasn’t a bug in a complex neural network; it was a deliberate placeholder I had forgotten was there—a developer-induced hallucination.

// Simulates calling the Gemini API to analyze answers and generate reports.

async function analyzeAnswersWithAPI(answers) {

console.log(“SIMULATING API CALL to analyze answers with key:”, geminiApiKey);

// Here, a real app would send the questions and answers to the API…

return new Promise(resolve => {

setTimeout(() => {

// THE HALLUCINATION STARTS HERE:

const score = Math.floor(Math.random() * 16) + 30; // 1. It generates a random high score.

const analysis = {

score: score,

summary: “The candidate demonstrates strong problem-solving and adaptability skills…”, // 2. It uses hardcoded positive text.

greenFlags: “Clearly structured answers (STAR method used), shows resilience…”, // 3. It fabricates positive details.

redFlags: “Answers related to data analysis were more anecdotal…”

};

resolve(analysis);

}, 1500);

});

}

My app wasn’t “thinking” at all. It was performing a magic trick.

- It ignored the user’s input entirely.

- It generated a random high score between 30 and 45.

- It confidently presented pre-written, positive feedback as a genuine analysis.

This was a prototype’s shortcut, but it was a perfect microcosm of the bigger problem. My simple app, in its rush to provide a slick-looking output, created a complete fiction. It highlights a critical danger: we are building systems so complex that we are beginning to trust their output without being able to verify their process. My app was a simple box I could open. A true Large Language Model is a black box of trillions of parameters, almost impossible to fully dissect.

When an AI goes wrong, it doesn’t just crash. It can fail by becoming a perfectly articulate, confident, and utterly convincing liar. And as we integrate these systems into our legal, medical, and financial institutions, the consequences of trusting their hallucinations could be catastrophic. My little experiment was a harmless failure. The next one might not be. Thus “The greatest danger of AI isn’t its errors, but its unwavering confidence in them.”

Bibliography:

1. Bohn, Dieter. “Google’s AI Chatbot Bard Makes Factual Error in First Demo.” The Verge, 7 Feb. 2023, www.theverge.com/2023/2/8/23590864/google-ai-chatbot-bard-mistake-error-exoplanet-demo.

2. Santora, Marc. “New York Lawyers Sanctioned for Using Fake ChatGPT Cases in Legal Brief.” Reuters, 22 June 2023, www.reuters.com/legal/new-york-lawyers-sanctioned-using-fake-chatgpt-cases-legal-brief-2023-06-22/.

3. Franck, Thomas. “AI: Judge Sanctions Lawyers over ChatGPT Legal Brief.” CNBC, 21 June 2023, www.cnbc.com/2023/06/22/judge-sanctions-lawyers-whose-ai-written-filing-contained-fake-citations.html.

4. Vincent, James. “Microsoft’s New AI Chatbot Has Been Saying Some ‘Crazy and Unhinged’ Things.” NPR, 1 Mar. 2023, www.npr.org/2023/03/02/1159895892/ai-microsoft-bing-chatbot.